Baking delicious cloud instances

Nowadays, configuration management is getting the backseat on the cloud infrastructure ride.

With immutable and phoenix servers rising in demand, we tend to see more and more shell scripts taking the spotlight on instance configuration, where Dockerfiles are the supreme example. However, this post is not about containers.

periodic reminder. Immutable means can't change not don't change

— Gareth Rushgrove (@garethr) June 7, 2017

Let’s put immutable servers aside for a moment and focus on phoenix servers and how to deal with their configuration at boot time, I started thinking there must be a simpler and efficient way to manage their configurations.

Amazon Web Services

During my career I’ve worked with bare metal servers, XEN and KVM virtualization, LXC containers and private cloud environments like VMware vCloud and Openstack. This year, I’ve been looking more closely into Amazon Web Services (AWS), so that’s what I’ll be addressing here.

So far I’ve seen a couple of patterns:

- Bake an Amazon Machine Image (AMI) adding a complex shell script to take care of the final provisioning at boot time.

- Ship the AMI with all the environment configurations and, at boot time, just load the correct one, depending on the environment where it’s spun up.

No matter which one you choose, you’ll be left with the same problem: the need to build the AMI baking process and, afterwards, getting the final configuration to run at boot.

One could argue that service discovery could address the latter, but you would still need to take care of interfacing it with your service. Most of the services out there don’t support service discovery… yet. So I won’t dwell into that right now.

Configuration Management

For the past few years I’ve been using Chef and Ansible in complex environments, authored several Chef cookbooks, recipes and providers as well as Ansible playbooks, roles and modules. As such, I have strong opinions regarding each one of these tools. In a nutshell:

- Chef has a steep learning curve and it’s hard to get your head around it, but it allows easy management of complex scenarios by having ruby exposed alongside the domain specific language.

- Ansible is dead simple to learn and teach, but quickly becomes problematic when complexity needs to be addressed. “Coding” YAML is a pain and Jinja templates are not a walk in the park either. On the modules’ side python helps quite a lot.

OH: "Principal YAML Engineer"

— Joel (@kintoandar) June 10, 2017

Don’t get me wrong, I really appreciate these tools and most of the deployment orchestration I’ve helped build ended up using both, taking advantage of the strengths of each.

Keep in mind that choosing a technology shouldn’t be taken lightly and you must consider the impact on the organization, so truly scrutinize what best suits your requirements. Running after the next shiny tool/hype, the language you feel more comfortable with or the agile framework ‘du jour’, is meaningless in comparison with the overall company growth you seek, or should aspire to.

Regardless, nothing beats a shell script, right?

If you’re the only one managing the system, sure, but if your goal is to provide the tooling for everyone to use, maybe not so much.

Becoming someone like Brent (The Phoenix Project IT ninja and all around entreprise bottleneck) is not an option. In order to support the systems’ growth and therefore the business prosperity, we need to ensure technical knowledge is distributed and that everyone is able to modify, improve and use the tooling we build.

Infrastructure Management

Tools like Terraform try to fill the gap on infrastructure orchestration as a whole, but I wouldn’t call it configuration management per se, at least regarding the instances. Assuming your instances reside inside a private subnet, the interaction provided sums up to the user_data configuration, injecting a cloud-init script.

Cooking up a plan

All this got me wondering… What do I want out of this?

- DRY up the process

- Anyone should understand and feel empowered to modify the baking scripts and the final provision ones

- Improve code reusability

- Environment parity

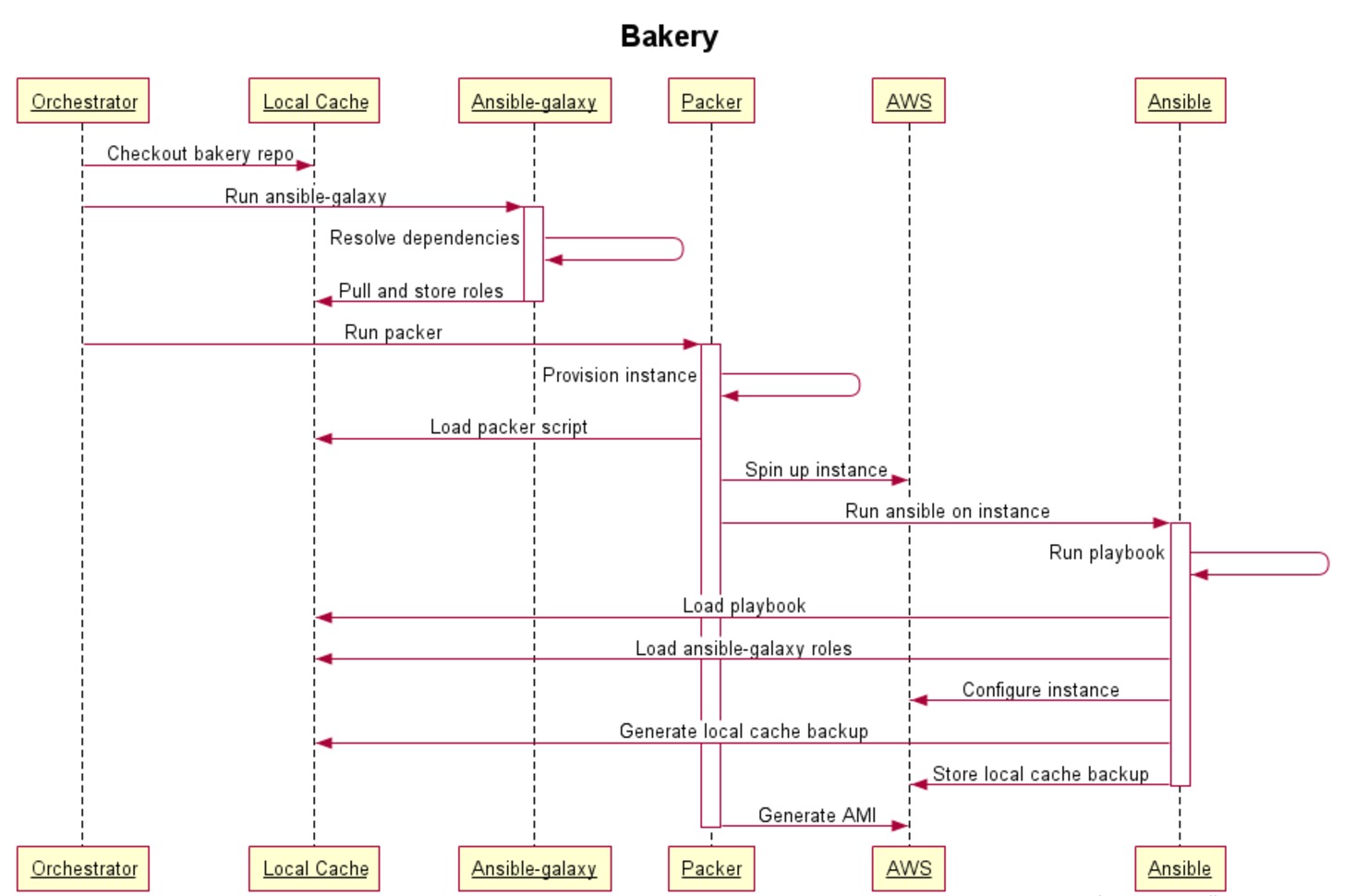

When I got to this list, I started by figuring out how could I meet all of the above and ended up designing a workflow from scratch to achieve all requirements. The following sequence diagram illustrates the workflow:

Disclamer: Being totally honest, my preference would have been Chef instead of Ansible. But since I want more people involved and contributing, I’ve looked for a way to reduce the entry level on the required configuration management knowledge. As described above, I opted for Ansible, trying to keep things simple and straightforward to ease the onboarding of other collaborators.

Components

This workflow has a few core components, each one with a set of tasks and inherent responsibilities.

Orchestrator

Where all the tasks are triggered, so pick your poison:

- Jenkins

- Travis

- Thoughtworks Go

- …

Local Cache

Where the project repository is checked out and all dependencies are stored. This path will be backed up and sent into the AMI at /root/bakery by our Ansible playbook.

When the AMI is instantiated using our cloud-init file, the Ansible playbook will be ran again, now locally, but as the override cloud_init will be enabled a different flow will be performed.

Ansible-galaxy

If you’re familiar with the awesome Berkshelf and berks vendor, ansible-galaxy has a similar purpose to resolve Ansible roles dependencies and create a local copy of them.

You can even use private repos instead of publicly available roles, if that’s your thing. Here’s an example:

~ $ cat requirements.yml

---

- src: git@github.com:PrivateCompany/awesome-role.git

scm: git

version: v1.0.0

name: awesome-roleYou can download all the required roles using:

ansible-galaxy install -r ./requirements.yml -p ./rolesAnsible

Improves code reusability through roles. Makes configuration templating much easier instead of using cryptic sed one liners (even though ❤️ regex).

If the roles have concerns separated per task file, it’s possible to call the templating features separately from the installation ones. This will truly help split the code workflow for the baking and the final configuration at boot up.

Packer

More about it on a previous post.

Tasting some baked goods

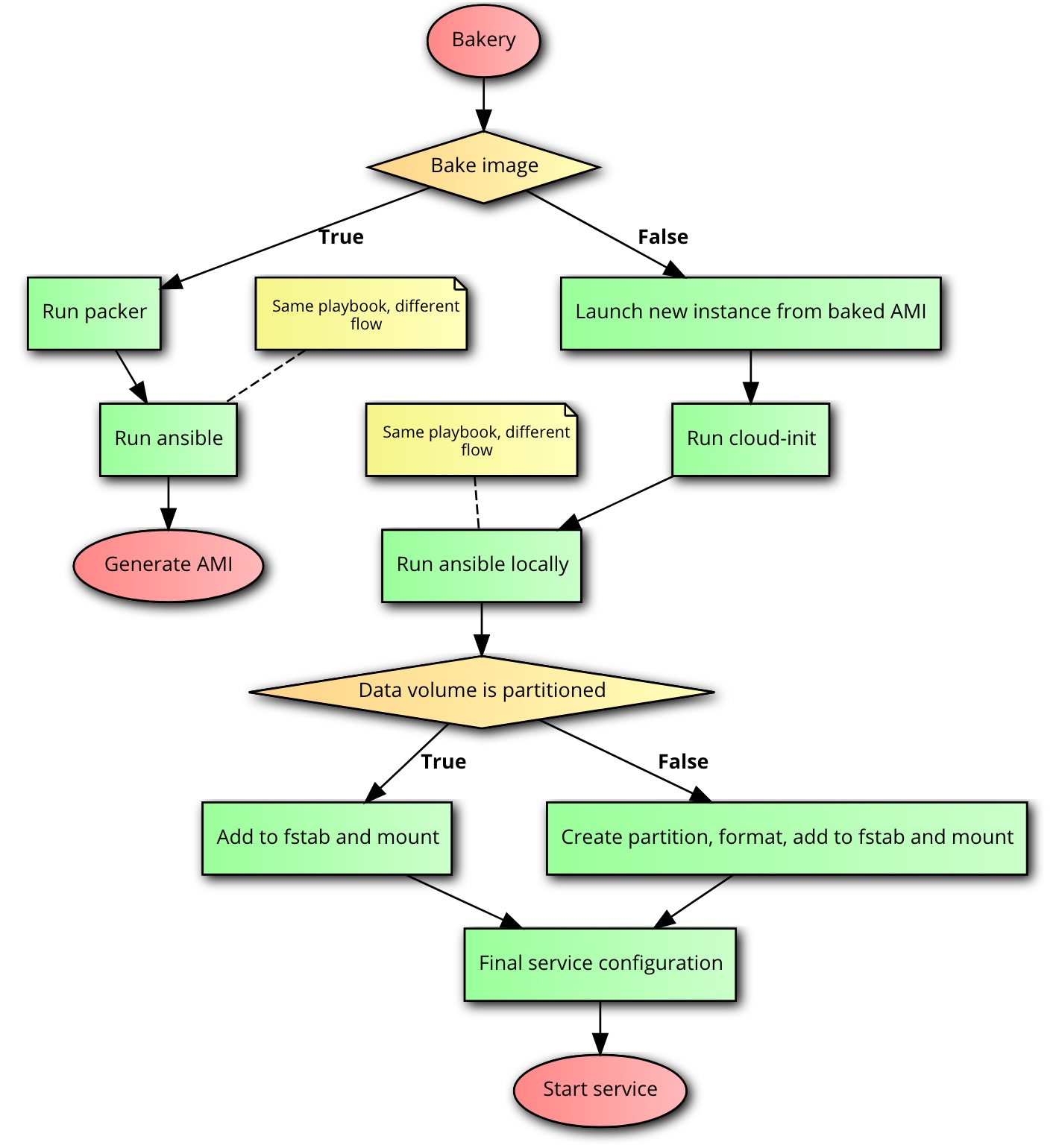

With this approach, the code used for the AMI’s bake is the same as the one used on the final provision during boot up. The only difference is the code flow on the playbook between the two steps.

I’ve built a small example to demonstrate how everything comes together so you can try it out. Obviously, this is far, far away from production ready but you’ll get the gist and it’ll make the entire workflow much clearer.

In this example we want to spin up an instance with Prometheus using a separate data volume, useful for instance failures and service upgrades. The flow is something like this:

Requirements

This demo has the following requirements:

- AWS API access tokens

- Packer >= 1.0.0

- Ansible >= 2.3.0.0

Mixing the ingredients

For generating an AMI to use in this workflow you just need to run:

# Get the repo

git clone https://github.com/kintoandar/bakery.git

cd bakery

# Download ansible roles dependencies

ansible-galaxy install -r ./requirements.yml -p ./roles

# Use packer to build the AMI (using ansible)

export AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

export AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

packer build ./packer.jsonNow, to test the new AMI, just launch it with an extra EBS volume and use the provided cloud-init configuration example as the user-data. After the boot, you can check the cloud-init log in the instance:

less /var/log/cloud-init-output.logBe sure that /root/bakery/cloud-init.json was created with all the required overrides for Ansible, specially the cloud_init=true.

Profit!

You may destroy and attach a new instance to the separated data volume and Ansible will take care of the logic of dealing with it.

Using Terraform to manage those instances becomes easier: you only need to take care of templating the cloud-init file and attach the volume to the instance. You may find here an example of a cloud-init configuration that you can use to template.

Here’s an example of a Terraform script:

Pro tips

- You could pass Packer a json file with overrides for Ansible to use during the bake process, taking advantage of --extra-vars.

- Terraform aws_ebs_volume allows using a snapshot as the base for the data volume, which is quite useful in case of a major problem that forces you to rollback the data volume to a consistent state.

Ready to be served

I wouldn’t say this is the best workflow ever, but it does check out all the requirements I had. I’ll keep you posted on how it goes.

Happy baking!

🍰

Leave a comment